I just want to thank you all for the wonderful packet of handmaid cards and letters that you all sent me for my birthday. I enjoyed them a great deal. I sat on my bunk and read them all through and said a prayer for each and every one of you, and your teachers.

I have some good internet at the moment, so I thought I would share some pictures and stories about the Philippines for you guys.

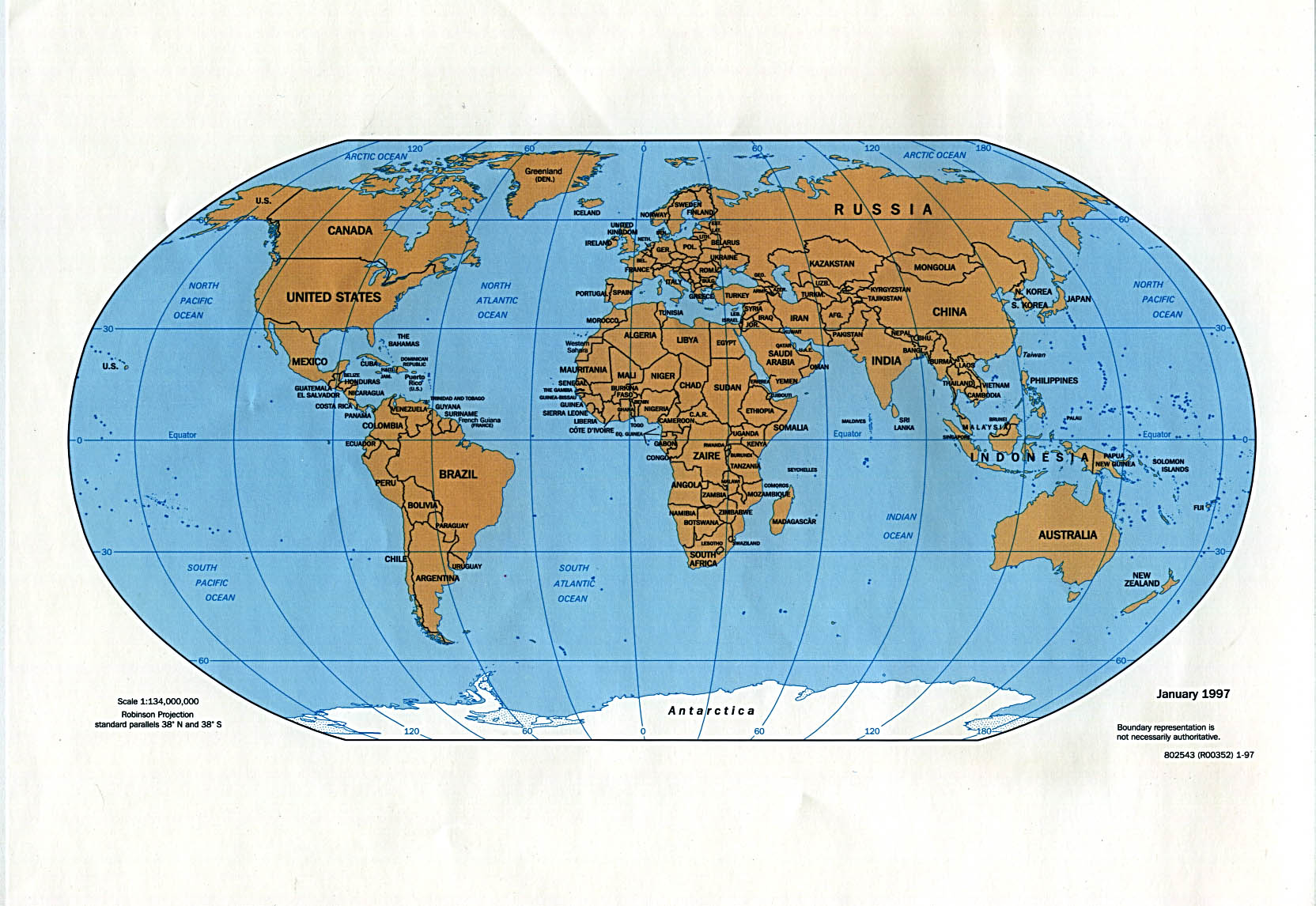

First off, if you don't know where the Philippines are, you should start there.

On the map you first find Asia, then you move southeast of Asia into the Pacific ocean, and in the middle of the Pacific ocean you will find a group of islands that look like this:

For security reasons I can't really tell you guys where I am in the Philippines, but I can show you some pictures I took.

I like sunsets. They look different in all the different countries I have been to. Actually, believe it or not, Iraq and Afghanistan had some of the most amazing sunsets I have ever seen, because of the high dust content in the air. I saw similar sunsets sometimes in New Mexico. Why do you think dusty air makes great sunsets?

This is a statue of Lapu-Lapu (yes, that is really his name, one of many names, in fact) who was a tribal king on an island called Mactan who commanded the local warriors in a battle on April 27, 1521. Ferdinand Magellan was killed in that battle. It did not prevent the Spanish from taking over the Philippines, but hundreds of years later Lapu-Lapu is regarded as the first Filipino national hero.

This dish is called "lechon," and it is delicious. The pig is stuffed with coconut leaves and all sorts of veggies and herbs I would not be able to name. It is then roasted slowly in an oven with the skin still on it. It is quite fatty, fully of cholesterol, protein, and other delicious things that growing soldiers require.

This dish is called "a tuna fish." That particular fish is approximately a meter and a half long, and weighs about 50 kilograms. There is an art to carving the fish like that. They slice it deep with a very thin, sharp knife in lengthwise slices, then again, parallel to the spine, and then perpendicular to the body, to create hundreds of little slices, each one about half an ounce in size. Then you eat it, raw, with chopsticks. I probably at about a kilo of it myself.

I took this picture while snorkeling in the ocean.

And this one. The clownfish likes to live inside the anemone, which has tons of stinging fronds that wave in the current. They don't bother the clownfish, but they sting any bigger fish that try to eat it. This is a symbiotic relationship.

What does the shape of this mountain tell you about how the islands were formed?

That's me.

These little motorbike taxis are one of the primary means of transportation in most of the cities.

This field is about 300 acres of rice. Rice is one of the most important foods in the world. It makes up 90% of the grain diet of many countries in Asia. It needs to be completely submerged in water for part of its growing cycle, so it is grown only on flat plots of ground. However, in the volcanic hills of southern Mindanao, and in the Himalayas in Nepal, I have seen rice grown on the sides of steep hills and mountains. They overcome the terrain by carving levels of terraces out of the side of the mountain like giant steps going up the mountain.

The amazing thing about rice is that it is still planted by hand throughout much of the world! The fields (called "rice paddies") are flooded with muddy water, and then workers walk through the fields, painstakingly sticking shoots of rice into the mud, one at a time. It is a labor intensive, time consuming process. A lot of countries use migrant workers, including children your age, to do this work, paying them 50 pesos ($1.10) per day. It takes hundreds and hundreds of workers to plant fields this size.

Baskets at a market, made out of palm fronds and bamboo leaves.

A market at a "Peace Village" promoting cultural sharing between Muslims and Christians. Most people do not know this, but there is a Muslim insurgency going on in the Philippines, but unlike other places in the world, there are strong peace processes in the works, and some legitimate reconciliation does seem to be happening.

Traditional wooden dishes, palm baskets, and work knives, with a couple of traditional swords.

This is what the mountains look like from the air. They are not very tall, compared to the Rockies or the Himalayas, but they are extremely steep and covered with jungle. They are left over from the volcanic activities that formed the islands. They are also beautiful!

I hope you enjoyed all the pictures. Thank you so much for the cards and the letters. Be good in school.

Yours Truly,

Ryan Kraeger

Showing posts with label Philippines. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Philippines. Show all posts

Monday, February 17, 2014

Friday, February 14, 2014

White People Be Crazy

After Mass this morning I went for a run. There was something ironic about that fact, in and of itself, at least to my mind. The priest who said Mass was a short, heavy Filipino man with a crutch and a cane. He walked as if his left knee had been fused, or maybe his left leg was a prosthetic, and he had a large, heavy gut, and a cheerful, pleasant smile. I watched him laboriously make his way down the steps behind the church from the rectory, and then process down the aisle, step, thump, peg, step, thump, peg, step, thump, peg.

Now I have a chronic case of what my younger brother calls, "Lone Survivor Guilt," meaning if I see someone else worse off than I am in any way, I immediately feel bad that I have what they do not. I immediately and irrationally felt bad for having two good legs. God is patient with me though, and through the course of the Mass He slowly drew me instead to thankfulness of the courage and determination that made that man climb steps and walk up aisles and do other things that I take completely for granted, to bring me the Holy Sacrifice. To reproach myself for what I feel like I am not doing is to make it all about me. To thank God for what he is doing, is to make it all about God. One leads to depression, selfishness, fear, and lack of confidence. The other leads to peace, joy, gratefulness and trust.

So I went for a run after Mass, as I had planned. I was much slower than I would like to be, and I ran a hot spot into the crease of each big toe, which I am happy for, since I can offer it up for people who don't have feet! Is it anything on the same or equivalent level to their sufferings? No. It is what God has given me, though.

On the way back I ran past this guy:

The sign painted on the back of his garbage cart caught my eye. When I asked him if I could take a picture of it he smiled at me with a big, peaceful smile, like: "This crazy white guy!"

"Thank you Lord God for the life & grace, the love & peace, the health & strength, THE NAME of Our Lord Jesus."

Sometimes God gets obvious.

After my run I did some yoga in the hotel gym. There were some other guests there, including one middle aged gentleman trying to get a workout, but his little girl kept running in from the pool to talk to him. She was staring at me like I was the circus!

I can understand that, though. I am big, very hairy, and when I workout I am very sweaty. I am not particularly flexible or coordinated, although not bad for my size. All in all, I look pretty odd doing yoga. When I do yoga in white people gyms I always kick the heavy bag a few times afterwards as a way of forestalling any comments.

This little girl was watching me like saturday morning cartoons and talking with her daddy in Visayas. I imagine the conversation was something like, "Daddy, look at the big sweaty white guy! What is he doing?"

"I don't know, honey. White people be crazy."

God bless you all, this fine day. Remember to be grateful.

Now I have a chronic case of what my younger brother calls, "Lone Survivor Guilt," meaning if I see someone else worse off than I am in any way, I immediately feel bad that I have what they do not. I immediately and irrationally felt bad for having two good legs. God is patient with me though, and through the course of the Mass He slowly drew me instead to thankfulness of the courage and determination that made that man climb steps and walk up aisles and do other things that I take completely for granted, to bring me the Holy Sacrifice. To reproach myself for what I feel like I am not doing is to make it all about me. To thank God for what he is doing, is to make it all about God. One leads to depression, selfishness, fear, and lack of confidence. The other leads to peace, joy, gratefulness and trust.

So I went for a run after Mass, as I had planned. I was much slower than I would like to be, and I ran a hot spot into the crease of each big toe, which I am happy for, since I can offer it up for people who don't have feet! Is it anything on the same or equivalent level to their sufferings? No. It is what God has given me, though.

On the way back I ran past this guy:

"Thank you Lord God for the life & grace, the love & peace, the health & strength, THE NAME of Our Lord Jesus."

Sometimes God gets obvious.

After my run I did some yoga in the hotel gym. There were some other guests there, including one middle aged gentleman trying to get a workout, but his little girl kept running in from the pool to talk to him. She was staring at me like I was the circus!

I can understand that, though. I am big, very hairy, and when I workout I am very sweaty. I am not particularly flexible or coordinated, although not bad for my size. All in all, I look pretty odd doing yoga. When I do yoga in white people gyms I always kick the heavy bag a few times afterwards as a way of forestalling any comments.

This little girl was watching me like saturday morning cartoons and talking with her daddy in Visayas. I imagine the conversation was something like, "Daddy, look at the big sweaty white guy! What is he doing?"

"I don't know, honey. White people be crazy."

God bless you all, this fine day. Remember to be grateful.

Labels:

children,

daily life,

Daily Mass,

homeless,

morning,

Philippines,

poor,

running

Thursday, January 2, 2014

A Good Morning

Yesterday morning I attended Mass at 5:45 at a beautiful

church about a mile from my hotel. I walked there, as it is not that far and

the weather is quite decently cool in the twilight before the sun comes up. The

church was not only beautiful, but quite huge as well. The congregation seemed

little disposed to sitting close to each other, but instead were scattered

fairly evenly throughout the whole church, with only a slightly higher concentration

near the pulpit. There might have been a hundred and fifty people or so, but in

the vast hall that seemed like a tiny number, barely a handful. There is always

room for more in the Kingdom.

That same church has to hold six Masses every Sunday to accommodate

all the worshippers. I have seen the 5:00 PM English Mass filled to

overflowing, every stone bench and plastic chair in the courtyard likewise

filled, and only room to stand, with a crowd waiting outside the gate for the

Tagalog Mass to start.

This particular morning there was a young fellow in a white

cassock behind me. It was the same cassock as the priest wore, but he looked

too young to be a priest. Then again, you never can tell with Filipinos, and he

was praying the Divine Office from a very shiny and new looking breviary. So I

asked him, “Are you a priest?”

His face lit up in such a smile. He replied, “No, not yet. I

am just a brother,” but he was tickled pink to be asked. There was something

childlike about his excitement. It was obvious, shining from his face, that he

wanted with all his heart to be a priest and that he will, God willing,

continue on attending Mass and praying his Office and studying and working

until he receives that great gift.

Leaving from the church I started to walk home. The sun was

already excruciatingly bright (I had not brought sunglasses) and the

temperature was in the upper 80’s, on its way up. I stopped at a bakery shop

where a little beggar girl with a baby appealed to me for some coins. I bought

two bibingkas from the shop, thereby providing free entertainment for the two

girls watching the register. They thought I was quite funny for some reason. I

ate one of the bibingka, and gave the other one with a few pesos worth of coins

to the beggar. She looked like she could use it. I usually avoid giving coins

to the children, because most of them are handled by professional beggars who

take all of the profits and the kids get the scraps, but in this case I saw a

woman across the street that had been talking to the girl, and I took her to be

the girl’s mother. Not because women cannot be pimps or exploiters, but because

she was not dressed any better than the little girl. At any rate she got the

coins and the bibingka, and a few prayers.

Leaving from the church I started to walk home. The sun was

already excruciatingly bright (I had not brought sunglasses) and the

temperature was in the upper 80’s, on its way up. I stopped at a bakery shop

where a little beggar girl with a baby appealed to me for some coins. I bought

two bibingkas from the shop, thereby providing free entertainment for the two

girls watching the register. They thought I was quite funny for some reason. I

ate one of the bibingka, and gave the other one with a few pesos worth of coins

to the beggar. She looked like she could use it. I usually avoid giving coins

to the children, because most of them are handled by professional beggars who

take all of the profits and the kids get the scraps, but in this case I saw a

woman across the street that had been talking to the girl, and I took her to be

the girl’s mother. Not because women cannot be pimps or exploiters, but because

she was not dressed any better than the little girl. At any rate she got the

coins and the bibingka, and a few prayers.

I did not give any coins to the three little boys who hailed

me at the next stop because they were obviously hale and hearty and well fed,

and were just curious to see a big bald white guy on their street and thought

they might get some free pocket change.

I hailed one of the little motorbike side-car taxis and

caught a ride back to the hotel, because it was getting hotter and sunnier out.

The taxi driver asked where I was from and practiced his English, which, while

not good, was way better than my Tagalog. When I got there I asked him how much

I owed him, and I could see him hesitate. The real rate is 8 pesos for anywhere

in the city, but I was white, and he knew I could afford more. He didn’t know

whether or not I knew what the rate should be. Perhaps he wanted to make up a

higher number and couldn’t think of one, or perhaps he was just too honest. At

any rate I just asked, with my most “innocents abroad” white guy look, if 20

pesos would be okay. His eyes lit up and he thanked me profusely and wished me

a happy New Year.

The guys like to laugh at me for doing stuff like that. They

pride themselves on knowing the going rates and not letting the locals get over

on them. I, on the other hand, get fleeced pretty regularly. I hate bargaining

and I am not good at it. It just seems like a waste of time to me.

The guys like to laugh at me for doing stuff like that. They

pride themselves on knowing the going rates and not letting the locals get over

on them. I, on the other hand, get fleeced pretty regularly. I hate bargaining

and I am not good at it. It just seems like a waste of time to me.

20 pesos is less than 50 cents. I don’t even carry loose

change in America. I toss that kind of money into a jar for years and never

miss it, and then eventually I give the jar away rather than go through the

bother of counting and banking it. Here I can give some driver 50 cents and a

friendly smile and conversation and totally make his day. That seems worth it

to me.

Labels:

beggar,

charity,

daily life,

food,

Mass,

money,

Philippines,

poor,

priesthood

Wednesday, January 1, 2014

Christmas Eve Feast

After Christmas Eve Mass I went out looking for some food.

This town does not stay open late. The hotel would still have food at 10:00,

but it would be approximately 1500 pesos for the Christmas Eve feast. I have

found that two blocks from the hotel, the price of everything drops to about

25% of what it costs at the hotel and mall.

I found a little barbecue restaurant with a truly charming

wait staff (one delightful young man was hocking loogies into his hand in front

of my table) but the smell and the price was right. I looked over the menu and

saw that they offered 100 grams of tuna belly for some 45 pesos, and about the

same for 100 grams of squid. Now, I love both tuna belly and squid, and since

100 grams is not that much, barely more than a few good mouthfuls, I ordered

one of each, plus an order of “Native Style Barbecue Chicken.”

(Carbs, you say? We don’t need no stinkin’ carbs!)

The waitress gave me a funny look, which you would think

might have clued me in, but then again I always get funny looks when I order

food in Asia. (I don’t always order food in Asia, but when I do, I get funny

looks.)

Well, in due course the food arrived. The first plate was

the grilled tuna belly. It was not 100 grams. It was 500 grams. That is about

18 ounces of fish. I was paying for it at the rate of 45 pesos/100 grams, and,

while you can’t beat the price, 18 ounces is a fairly respectable amount of

fish.

When the squid arrived it was, likewise, a hot plate of 500

grams of squid. I love me some fresh grilled squid as much as the next guy,

especially the way the Filipinos serve it, stuffed with pico de gallo or mango

salsa, but I was now looking at a full kilo of seafood, and my chicken hadn’t

even arrived yet!

Fortunately, while the chicken was an entire upper shoulder

and wing skewered on a bamboo skewer, it was from an anorexic chicken. I doubt

I got much more than a few ounces of meat off of that.

What is a man to do, in such a plight, but begin at the beginning

and going on until he gets to the end of it? Washing it all down with fresh

mango juice also helps. (See? I am not totally opposed to carbs!) It was

delicious, nutritious and very, very filling.

Yes. This sort of thing happens to me. All the time. You get

used to it eventually.

Labels:

Christmas,

daily life,

food,

meat,

odd occurrences,

Philippines,

street food

Sunday, December 29, 2013

God Must Love Weird People... He Makes So Many of them!

I walked up to Mass one day during Simbang Gabi. It was

dark, of course, being 4:20 AM, or thereabouts. The church and plastic lawn

chairs all being full as per usual, I sat down on the stonework of the

flowerbed and began saying Lauds.

A Filipino man sat down next to me. He was an older

gentleman, perhaps in his late fifties or early sixties. It is hard to tell

with Asians. He had a long, scrawny neck, big ears and nose, and that

not-entirely-aware, slightly dissipated look that I associate with chronic

alcoholics. He wore a pair of jeans with holes in the knees, and a ratty

t-shirt, and flip-flops, and no one else in the congregation paid him any

attention whatsoever.

He sat down next to me and looked me over for a few minutes,

and then smiled and began speaking to me in Tagalog. I looked up at him and

smiled politely, and listened with no comprehension whatsoever. He went on and

on, with gestures and significant looks and conspiratorial nods. Finally he

said the word, “Tacloban,” with an interrogative upward inflection.

“Tacloban?” I asked, “Yes, I was at Tacloban.”

He nodded knowingly, and went off on another conversational

paragraph of Tagalog. Eventually he finished it up with an English sentence,

“What is your country of origin, Sir?”

“America,” I said.

“Ah!” He smiled. More Tagalog, more gestures and nods of

comradarie. “Are you single?”

“No. I am engaged.”

He exclaimed, “Ah!” and slapped his thigh. More Tagalog, and

a couple of winks. “So you are filing for divorce?”

I think maybe at this point my face showed something other

than polite attentiveness. “No.” I answered quite emphatically. I didn’t know

but that he might be trying to hook me up with a grand-daughter or niece or

adult themed dance-club, and I wanted to make sure that my status was quite

unequivocal.

He nodded with perfect comprehension. “One woman is enough

for you?”

“Yes,” I said. “One woman is more than enough for me.”

He soliloquized in Tagalog for another few sentences, but

with enough English scattered throughout that I managed to gather that one was

not enough for him. He had had to have two. There was also something about his

first wife, and a hope that she was like her. Who “she” and “her” were I have

no more idea than you do.

Then he looked at me with the shrewd look of someone who has

rapidly seen through an opponent's clever but misguided attempts to pull the

wool over his eyes. “Do you understand the dialect of the Pilipino people?”

“No.” I answered. No good trying to trick this guy! May as

well just out with it.

The Mass started at this point. He sat next to me for the

sitting portions, but for the rest of it he was somewhat unpredictable. He

would sidestep throughout the crowd of parishioners, periodically dropping to

one knee on the cement pad for a few seconds, and then rising back to his feet.

No one else even gave him so much as a glance, except for some of the teenagers

who laughed at him a bit.

The Mass was mostly in English, but the homily was in Taglish,

an approximately 90/10 mix of Tagalog and English. He came back over and sat

down next to me and asked, “Do you understand what he is saying?”

I shook my head and said, “No, I do not.”

So he undertook to translate the homily for me. His method was

somewhat unorthodox, but surprisingly effective. He would sit with his head

bowed and his arms folded, a studious expression on his face, listening for the

space of a sentence or two. Then he would say an English word or two, combined

with a knowing wink and a hand gesture. Sometimes he would say a Tagalog word

and then give me the English translation, and do this several times, as often

as that word was repeated. Sometimes he would sigh and just gesture

expressively with his hands. I would say I understood about 20% of the gist of

that homily, and enjoyed the whole thing immensely.

He did not speak to me much more for the rest of the Mass,

except to share a few choice lines from some of the hymns, but he wished me a

very heartfelt “Merry Christmas!” at the end of it. He nodded and smiled and

waved as he walked off, for all the world as if he possessed some incredibly

enjoyable secret which he had just let me in on.

I have seen him there at Sunday Mass since, but have not spoken with him. He always arrives, sits, and leaves alone. I don't know his story, and although I am sure it has had its darker moments, yet there is some kind of faith there, I am certain of it. May God Bless Him and bring Him safely to his heavenly home!

Labels:

language,

Mass,

odd occurrences,

old people,

Philippines

Thursday, December 26, 2013

Simbang Gabi

Being in the Philippines over advent has been an incredible

opportunity for me to take part in the Simbang Gabi tradition that is

celebrated by Catholic Filipinos all over the islands. Indeed it is practiced

all over the world as well. My Filipino friends in Tacoma all have Simbang Gabi

celebrations at some of the most heavily Filipino parishes throughout the city.

Starting on the 16th of December they have a Mass every day,

sometimes with processions and lanterns, which continue until the 23rd.

The final Mass is the Christmas Vigil for a total of nine Masses forming a

Novena leading up to Christmas.

Being in the Philippines over advent has been an incredible

opportunity for me to take part in the Simbang Gabi tradition that is

celebrated by Catholic Filipinos all over the islands. Indeed it is practiced

all over the world as well. My Filipino friends in Tacoma all have Simbang Gabi

celebrations at some of the most heavily Filipino parishes throughout the city.

Starting on the 16th of December they have a Mass every day,

sometimes with processions and lanterns, which continue until the 23rd.

The final Mass is the Christmas Vigil for a total of nine Masses forming a

Novena leading up to Christmas. One thing I did not know about Simbang Gabi, (which means

“Night Mass,” also known by the Spanish “Misa de Gallo” or “Mass of the

Rooster” is that it is celebrated at 4:30 in the morning, at least in the

churches I attended. In Tacoma the celebrations are in the evening. I guess it

is hard to get Americans to do anything at 4:30 in the morning.

One thing I did not know about Simbang Gabi, (which means

“Night Mass,” also known by the Spanish “Misa de Gallo” or “Mass of the

Rooster” is that it is celebrated at 4:30 in the morning, at least in the

churches I attended. In Tacoma the celebrations are in the evening. I guess it

is hard to get Americans to do anything at 4:30 in the morning.

The first Simbang Gabi Mass I attended was on the 16th,

and I was amazed. I arrived at just

about 4:10 AM, but even then the church was

already full. The Filipino Churches I have seen are all alike in that they are

not built with solid walls like churches in the west. Instead they are built

with pillars supporting the ceiling and forming the walls, and between the

pillars are built wrought iron grates. Some of these grates are solid panels,

others are doors. In fact, the Carmelite Monastery in Davao has no walls at

all, only a series of wrought iron doors, all wide open, and tied at full open

position with wires.  At 4:10 AM, not only was the church full, but plastic chairs

had been set up in crowds around three sides, and all of the chairs were full.

People were sitting on the curbs, steps, and stonework surrounding the flower

beds. This was not just true on the first day, but on every day of Simbang

Gabi, including the Christmas Vigil.

At 4:10 AM, not only was the church full, but plastic chairs

had been set up in crowds around three sides, and all of the chairs were full.

People were sitting on the curbs, steps, and stonework surrounding the flower

beds. This was not just true on the first day, but on every day of Simbang

Gabi, including the Christmas Vigil.

When I told my little brother about that on Facebook chat he

responded, “If only we had just a fraction of that faith here! Try getting

Americans out of bed to do anything at 4:30 in the morning, let alone go to

Mass.”

Now, I am not naïve enough to think that every one of those

Filipino Catholics was automatically a saint just because they go to Mass at

4:30 in the morning for 8 days every December. There is a strong element of

cultural Catholicism present in the Philippines, as there is in any country

historically Catholic, meaning that a large part of the popular practice can no

doubt be accounted for simply because that is just what everyone does. There

does not need to be any real conversion of heart for people to follow a custom

that all of their friends and family follow.

That being said, they show up. They show up really early in

the morning. The custom, while not guaranteeing conversion any more than any

other custom will, provides at least that much opportunity. Even though our

actions should follow from conviction, it is also true that, being human, our

convictions often follow from our actions. We do not have strong faith because

we do not act upon our weak faith.

Simbang Gabi was a chance for me to act, and

having acted upon a faith barely equal to the task of dragging me out of bed at

4:00 AM, my faith has become stronger, my desire for the Eucharist has become

deeper, my relationship with the God who kicked me out of bed has grown deeper.

It is only by responding to grace that we grow in our ability to be open to it.

Labels:

catholic worship,

Christmas,

culture,

Daily Mass,

Philippines,

Simbang Gabi,

tradition

Tuesday, December 24, 2013

Best Christmas Vigil Ever!

Last night (Filipino time) I attended the Christmas Vigil at the Carmelite Monastery in Davao City, Philippines. I had been attending the Simbang Gabi Masses for the previous nine days, minus a few, both there and in other locations around the country, but I was happy to be at this church for the Christmas Eve and Christmas morning Masses. Without a doubt, it was one of the coolest Christmas Vigils I have ever attended.

I arrived about 5 minutes after 8:00, (the Mass started at 8:30). The body of the church was pretty well full, but there were still stacks of chairs that had not been set out yet, so I grabbed one and set myself up at the back, in the portico on the right hand side, where I wouldn't be too much in the way for everyone coming in, but I could still see the altar by leaning a little to my right around the doorway.

Of course that only lasted until all the other seats were taken, all the rest of the space in the portico was filled, and there was a lady standing beside me without a seat. Of course I could not just sit there all comfy and let her stand. I feel certain my Mama would have sensed the disturbance in the force and contrived to find a way to give me The Look! from ten-thousand miles away. I have no idea how she would have done so, and I didn't wait to find out.

So of course I stood up and offered her my seat, and I stepped a few steps back behind the rows of plastic chairs. Unfortunately this also meant that I stepped out from under the arch of the portico ceiling. Wouldn't you know it, it was raining out there! I was able to take some refuge under the umbrella of the gentlemen whose view I blocked when I stood up (I can't help that I am roughly twice the average Filipino's size.) He was kind enough to hold his umbrella over my head the entire rest of the Mass. However, since there were two of us under there, my chest and shoulders somewhat encroached beyond the protective circle, and accordingly got rained on for the entire Mass. There also seemed to be a hole in the umbrella, somewhere in the vicinity of directly over the back of my head.

The choir, however, was awesome, and the crowds of Filipinos standing in the rain to worship the newborn King was such an incredible experience, I not only did not care, I felt like spontaneously enacting a remix of Gene Kelly's "Singin' in the Rain" routine, combined Piano Guys' style with "Angels We Have Heard on High."

Sometimes when I am sitting in a chair at the kitchen table, working at school, or a blog, or some other VERY IMPORTANT PROJECT!!!!! my fiancee' will come up behind me and kiss the top of my head, and I know that she wants me to pause what I am doing and look up into her face and see her for a second. Good things happen then.

The rain on my head is something like that. God wants me to pause and look up and see Him for a second, so that good things can happen.

Perhaps that is why He is taking all the hair off the top of my head, so that I can feel His touch more readily.

Blessed Be He!

Merry Christmas All!

I arrived about 5 minutes after 8:00, (the Mass started at 8:30). The body of the church was pretty well full, but there were still stacks of chairs that had not been set out yet, so I grabbed one and set myself up at the back, in the portico on the right hand side, where I wouldn't be too much in the way for everyone coming in, but I could still see the altar by leaning a little to my right around the doorway.

Of course that only lasted until all the other seats were taken, all the rest of the space in the portico was filled, and there was a lady standing beside me without a seat. Of course I could not just sit there all comfy and let her stand. I feel certain my Mama would have sensed the disturbance in the force and contrived to find a way to give me The Look! from ten-thousand miles away. I have no idea how she would have done so, and I didn't wait to find out.

So of course I stood up and offered her my seat, and I stepped a few steps back behind the rows of plastic chairs. Unfortunately this also meant that I stepped out from under the arch of the portico ceiling. Wouldn't you know it, it was raining out there! I was able to take some refuge under the umbrella of the gentlemen whose view I blocked when I stood up (I can't help that I am roughly twice the average Filipino's size.) He was kind enough to hold his umbrella over my head the entire rest of the Mass. However, since there were two of us under there, my chest and shoulders somewhat encroached beyond the protective circle, and accordingly got rained on for the entire Mass. There also seemed to be a hole in the umbrella, somewhere in the vicinity of directly over the back of my head.

The choir, however, was awesome, and the crowds of Filipinos standing in the rain to worship the newborn King was such an incredible experience, I not only did not care, I felt like spontaneously enacting a remix of Gene Kelly's "Singin' in the Rain" routine, combined Piano Guys' style with "Angels We Have Heard on High."

Sometimes when I am sitting in a chair at the kitchen table, working at school, or a blog, or some other VERY IMPORTANT PROJECT!!!!! my fiancee' will come up behind me and kiss the top of my head, and I know that she wants me to pause what I am doing and look up into her face and see her for a second. Good things happen then.

The rain on my head is something like that. God wants me to pause and look up and see Him for a second, so that good things can happen.

Perhaps that is why He is taking all the hair off the top of my head, so that I can feel His touch more readily.

Blessed Be He!

Merry Christmas All!

Labels:

Christmas,

God's love,

gratefulness,

joy,

Mass,

Philippines,

rain,

true love

A Sparrow Finds A Home

I love the way the Filipinos design their churches.

The walls are all gratings, usually left perpetually open, so that the church is continually open. Breezes come through, aided by oscillating fans, which is a low budget alternative to AC.

Other things come in as well, besides the parishioners.

And find a place to make a nest, near the altar of the Lord of Hosts.

And they make a joyful noise unto the Lord!

Thursday, November 28, 2013

Tacloban, Part VIII

Sometimes, even in the midst of a disaster

area you have to stop and notice the beauty.

Some people might think it a

mockery. How could there be beauty in the midst of so much suffering? How dare

we enjoy beauty, how dare we rest? Why are we not working still, pushing

ourselves, doing something to relieve

the suffering? There is no time for anything as frivolous as beauty. It merely

mocks the loss of the people who have lost everything.

But then I have to ask, is it really a mockery after all?

Or is

it perhaps a sort of message? Perhaps even an answer?

For behold, all will be well, and All will be well, and all manner of things will be most well.

Labels:

America,

army,

Army life,

beauty,

charity,

disaster,

human nature,

Marines,

Philippines,

relief efforts,

Tacloban,

typhoon,

volunteering

Wednesday, November 27, 2013

Tacloban, Part VII

-->

At any rate, there I was, and there I stayed

until morning. It took the whole rest of the day for the shriveled, macerated

look to go out of my hands, probably because it continued to rain more or less

constantly until about lunch, and the last rainstorm wasn’t until after 5:00.

By then, however, we had received a tent and were figuring out how to set it

up. Better late than never, right?

Was it worth it?

Totally.

|

| A concrete and rebar ammo bunker that got ripped apart by the storm surge. Really. |

We landed at Tacloban Airport with

not a clue what we were supposed to be doing. There were six of us and only two

of us had an explicit job. The Air Force CCT guys were suppose to assess the

airfield and get it up and running. The rest of us were supposed to support

them.

We had food and water to get us

until the next day’s resupply, but the weight restrictions had been so tight

and the Air Force CCT kit was so heavy, we had not been able to pack much of

anything else. No tent.

We did have six mattresses, little

foam pads, twin sized, wrapped in plastic. One of the guys had a hammock, which

he strung up in a baggage trolley, so I took his mattress and mine. I laid mine

out on the ground and set a heavy tuffbox on each end. Given that I am 5’9”

tall and the mattress was barely 6’ long, this shortened my bed considerably,

but the rain was coming on and I needed an overhead shelter. I laid the second

mattress across the top of the two boxes and weighted down the ends with

another box and some large rocks. As homeless shelters go, I’ve seen worse.

The rain started around 10:30 PM.

At first it was no more than a steady, cheerful shower, not too cold, just

exceedingly wet. I was stripped down to a pair of shorts and my Merrel Trail

Glove running shoes, which can get as wet as you like without being ruined, or even especially uncomfortable, so

I didn’t mind a little damp. That is fortunate, since I was destined to be

quite damp indeed before morning.

At first all I had to worry about

was the splashing of gargantuan raindrops in the puddles that rapidly formed

around my cozy little dwelling place. Then water puddled on the top mattress and it

sagged and when I moved it poured its burden off one edge, onto the bottom

mattress. In no time at all I was lying on my side in a puddle. My shelter

lasted about an hour before so much water soaked through the holes in the

plastic that the mattress was completely sodden, and began to drip

continuously. Then, just to put the cherry on top, it began to downpour torrentially. Yes. That is a word.

| |

| Home Sweet Home!! (There used to be another tuffbox holding up the left side.) |

I have spent more comfortable

nights, but all in all, it could have been worse. At least it was a warm rain,

and I had some overhead cover. You might not think that makes much of a

difference, but the truth is that it does. It is one thing to sleep in a

puddle, but when you are wearing next to nothing and it is warm enough, it

actually is not that bad. However, continually having torrential tropical depression

type rain pounding into you, splashing on your face, chest, back, legs, etc. that is

something else entirely. Each rain drop, in hitting you, emphasizes the overall discomfort, wakes you up again, and generally just brings your focus back to the here and now. I assure you it is hardly conducive to a restful

night’s sleep.

The worst thing was actually my

right hip. It turned into a pressure point because I was sleeping on my side

and didn’t have room to stretch out, and the mattress was only an inch and a

half of foam on cement. Apparently foam loses its cushioning ability when it is

saturated. Who knew?

Was it worth it?

Totally.

Labels:

America,

army,

Army life,

camping,

charity,

disaster,

human nature,

Marines,

Philippines,

relief efforts,

Tacloban,

typhoon,

volunteering

Tuesday, November 26, 2013

Tacloban, Part VI

-->

Blessings upon him and his family.

You know, people are beautiful,

crazy things. When I went back to camp to catch some sleep the night that we finally got the airfield moving at night, a Filipino man called out to me as I

walked by. “Hey, Sir!”

He was squatting on the concrete,

with his wife and their littlest baby squatting next to him, and six or eight little

dark eyed chitlins squatting all in a row behind him, along with some aunties or

big sisters or some such relative.

“Hey Sir,” he said again and

gestured to the line behind him. He was hopelessly at the back of the crowd,

and there was no way he was getting on an airplane tonight. But he had seen

lines of people being moved to the airplanes, and he had figured out what we

were doing and had separated his family and lined them all up in a row, ready

to go.

“Wow,” I said, “All lined up?”

He nodded and smiled hopefully and

his wife and babies all looked up at me with big, dark, hopeful eyes that just

made me feel like the biggest ogre on the planet for not getting them out right

away. (Okay, so I am a sucker for little brown babies with big brown eyes. So sue

me.)

What a leader! What a man! I could

see that he truly cared about his family, and keeping them together and making

sure they were safe was the most important thing to him. They trusted him. They

squatted in line behind him, one behind the other, keeping quiet and still and

cheerful among the chaos all around them.

What I would not have given to move

them right to the front of the line, right then! But I could not. That would

have caused a riot, in all likelihood, and that would have shut down loading

operations. I had to smile and say, “Good for you. Hang in there,” and walk

away.

When I went back again the next

day, they were still squatting there, all lined up, and he smiled at me

hopefully again. He was still cheerful, but he looked worn out. Other people

were still in line ahead of him. I had to get Marilee’s people out, because I

had promised, and I owed her. He watched that plane leave sadly, and moved his

family into the next spot.

After that I was no longer running

the airfield. The Marines had taken over now and I had to go do other things.

As I left for the last time, he smiled at me, still hopefully, but with a bit

more fear in his eyes. All I could do was point to the only seven rows of

people still in front of him, count them out and smile encouragingly, and then

walk away.

He was able to get his family out

later that afternoon, I think, because there were several planes in later that

day, and I didn’t see him again.

Blessings upon him and his family.

Labels:

America,

army,

Army life,

charity,

disaster,

fatherhood,

human nature,

leadership,

Marines,

Philippines,

relief efforts,

Tacloban,

true manhood,

typhoon,

volunteering

Monday, November 25, 2013

Tacloban, Part V

-->

I walked through the yard where

they were collecting the bodies of those killed by the typhoon. They bring them

in on trucks, collecting them from out of treetops along the beach, rubble

piles in the city, drowned vehicles along the street. A body bag hides a lot

about the person it contains, but it cannot hide the size. One old lady was

swelled up so huge they couldn’t zip the bag, so they left her with the bag

closed to her waist, one arm stiffened over her face, like she was trying to

block out the sun.

One body bag had a pair of business

shoes sticking out of a rip in the corner.

One body bag had only a single lump

in it. A two foot lump in a six foot bag.

The juices oozed out of them and

ran across the cobblestones. You cannot get sick from the smell. Death is not

contagious.

Only two feet long.

They only had a few trucks left

running. They needed them to haul bodies. They needed them to deliver food. So

they used the same trucks to do both. Fortunately a weird, twitchy, ex-Pat guy

who owns a pest control business donated his time, equipment and 300 gallons of

boric acid to spraying out the trucks between uses.

They wanted him to spray down the

cadavers at first. He told them it was a waste of time. Save the chemicals to

protect the living.

Another lump was just about four

feet long.

They do not have time to identify

them. At first a few were found and identified by relatives, but by now the

decomposition is too advanced. The National Bureau of Investigation is burying

them deep in a mass grave, in single file lines, with layers of lime and dirt

between each layer of bodies. Later, if they get the orders they may exhume

them and forensically identify them.

I think the mother of that tiny lump

would want to know.

Do you know how hard it is to get

cadaver smell out of your clothes?

I asked God, why?

I think He means us to ask. I think

He wants us to challenge Him for an answer. If we do not seek to know His

mind can we really have any part in Him.

Labels:

America,

army,

Army life,

charity,

death,

disaster,

human nature,

Marines,

Philippines,

questions,

relief efforts,

Tacloban,

typhoon,

volunteering

Sunday, November 24, 2013

Tacloban, Part IV

I got an incredible opportunity recently to go to the typhoon disaster

zone in the Philippines to help with relief efforts. The next few posts

are going to be a series, things I wrote to kind of decompress after

returning to my regular mission.

When we finally did manage to load

people at night it was almost accidental. We still had several hundred people

on the tarmac. Marilee’s group had long since been overrun and surrounded and

even though they had originally been first in line they were now completely

enveloped by this new crowd, and this new crowd was big, and not willing to go

back to their old places by the main gate. Airplanes were going to land all night

starting at 10:00 PM so I rushed down to the airfield after supper and started

trying to organize a night rescue. First I pleaded with the crowd through the

police guards, telling them that airplanes were going to be coming and going

all night, but that we were being told we could not load them if people were

going to be bum rushing them. I explained that if they could all be patient and

wait their turn, then we would be able to load many airplanes and get hundreds

of them out. If any of them pushed or tried to run around the line, we would

have to cut it off and then no one would get out until the next day.

The crazy thing is that it worked.

They were still panicky, and they still begged and pleaded to be put on the

airplane first, but there was very little pushing and shoving, very little

trying to sneak around the group to get in. Most of those who snuck around the

group to cut in line were officers and their families, who seemed to think that

the rules did not apply to them.

I had a Philippines Air Force

lieutenant who spoke excellent English and got the problem. He understood.

There was also an Air Force corporal, a lowly corporal with crazy poofy hair,

who likewise got the concept. Between them they were worth more than all the

senior officers on the scene put together. They were the ones doing the actual

work of setting up the police cordon around the crowd, directing police to the

areas they needed to be, deciding who was going to be pulled out of the crowd

first, setting them in lines of ten and keeping order among the lines. They did

the work of making sure the lines were single-file, and no one cut from one

line to the next. They were not afraid physically to grab people and set them

down where they needed them to be.

It is remarkable how little actual

work I did. A lot of running back and forth, seeing potential problems and

yelling them over the engine noise, directly into the ear of the lieutenant,

but they did all the actual work. Why did I get so tired then? Possibly

because, once again, I had been going for about 20 hours by the time I turned

in. It was worth it though. I had finally gotten a system built that allowed us

to load at night. It wasn’t really me building it, I just happened to be around

when a whole bunch of factors over which I had no control all came together,

and I saw that the time was right and we got to it and it worked. I was able to

teach it to two US Marine E-5’s (Sergeants) who took it and ran with it. I sometimes make fun of jarheads, but these two were good dudes, smart, compassionate, and squared the heck away.

One of them looked like the Terminator. Even I felt small next to him.

Between them and the Filipino Air Force folks, they loaded 250 more people between the time I went to bed at about 12:30 AM and 4 AM. When I checked back in with them the following midnight, they were still going.

That was a good night’s work.

Labels:

America,

army,

Army life,

charity,

disaster,

human nature,

Marines,

Philippines,

relief efforts,

Tacloban,

typhoon,

volunteering

Saturday, November 23, 2013

Tacloban, Part III

-->

I got an incredible opportunity recently to go to the typhoon disaster

zone in the Philippines to help with relief efforts. The next few posts

are going to be a series, things I wrote to kind of decompress after

returning to my regular mission. This is a long post, but I felt it was worthwhile to tell the whole story.

It is rare to meet someone who is

truly unselfish. It is the most humbling thing in the world, and, hopefully,

once you have seen it you will never be the same.

At the end of our second day on the

airfield, as we were trying to load up one of the last C-130’s that would be landing

during daylight hours, we almost lost control of the crowd. In fact, we did

lose control. 500 people pushed through the main gate, onto the tarmac and

began moving in a vast, desperate wave, straight for the front of the airplane.

The police managed to run and form a cordon around them and box them in before

they came anywhere near the running engines, but it was clearly too dangerous

to continue loading planes, especially once night fell and we could no longer

see the people. No pilot would even land with that many people on the tarmac.

We had to do something. The police

tried to push the people back, outside the main gate, but they wouldn’t go.

They had been standing in line all day, most of them, with no food or water,

and now, having finally reached the front, the tarmac, with freedom and safety

in sight, they could not bear the thought of spending the night there. Even

worse, they refused to be pushed back outside the main gate where they would

lose their places in line.

A Filipino lady named Gigi stepped

out of the crowd at this point, and said to me in excellent English, “Sir, I

know I am just a passenger, but these people do not want to go back out into

line because they are afraid of losing their places. Can you at least tell us

when the next plane is going to be here? We need to manage their expectations.”

“I do not know when the next plane

is going to arrive, and I do not know if we are going to be allowed to load

people. It will be too dangerous in the dark.” It was not a very convincing

answer, but she passed it back, and began working to try to convince the people

to cooperate. Another woman, named Didit, came out of the crowd to help, along

with a man whose name I did not get. Between the three of them, they did more

than the police to get everyone backed up. I found a room that used to be part

of the terminal complex, perhaps 40’ by 40’ and we convinced the crowd to back

into it. They didn’t all fit, and it must have been stiflingly hot and

claustrophobic inside, but at least they were off the tarmac.

I went to take care of a bunch of

other things, and when I came back, Gigi and Didit were busy organizing the

people, trying to get them to collect together by family and sit quietly. They

updated me on how the people were doing, (“Hungry, tired and thirsty,”) and

then introduced me to another civilian who had volunteered to help. They yelled

her name over the engine noise, so I didn’t quite catch it, but it had an “M”

and an “R” in it so I thought it was “Marina.”

She was a tiny Filipino lady in a red cross

shirt. She had been working her way through the crowd,

organizing the crowd into families and getting feedback from them on what they

needed, who had family or other contacts in Manila, and so forth. She was

short. When I say short, I mean she was short even for a Filipino lady. The top

of her head was about on a level with my chest, and she was completely

invisible until she stepped out of the crowd. She came right over to me,

grabbed my sleeve and pulled me down to her level so she could yell in my ear,

“Sir! These people need water right away. They are very thirsty.”

I had to laugh. I am not used to

being bossed around by people half my size, but she was taking their cause so

completely to heart she did not hesitate. I thought to myself, “Good Lord,

Woman, you are awesome.” Little did I know just how awesome she was, but I was

going to find out.

I promised to get them water, and then had

to break off to help unload the Malaysian planes that had just arrived. I

talked to the Malaysians about getting the people some water, and they agreed

to help, but they were taking their own sweet time about it. They came up with

a plan to provide biscuits for the people, but it took them fully an hour to

figure out that they had not brought any water in any of the pallets they had

brought. At that point I decided to take matters into my own hands. I talked to

the young US Marine Sergeant who was in charge of the forklift operators, since

he knew where all the supply pallets that came through the camp went and had a

solid idea what was on each one. I tell you what, that was a good kid. He knew

right where to find a mostly used pallet of water, and he sent his forklift

operator to go get it.

I talked to Gigi and explained that

water was coming, but that we could not have people charging out onto the tarmac

when it arrived. I needed her to come up with a system for distributing it in

an organized manner, so that everyone can get some water, all the way to the

back of the room. She said she would handle it, and she did. It was a thing of

beauty. After standing in the sun all day, most with no water of their own,

they passed the jugs all the way to the back first, disbursing them through the

crowd before anyone took any water. Then each person took one of the gallon

jugs, took what he needed for himself or his family, and passed it to his

neighbors.

The Malaysian planes did not take

anyone. When the two American planes arrived we tried to get permission to try

to load some people, but it was denied. The camp commander still felt it was

too dangerous. I passed the word to the civilian volunteers and they passed it

to their people, that everyone should just get some sleep. I cut a deal with

the Malaysians to get them some food, and they assured me they would get it

very soon. I went to sleep.

When I got back at about 6:00 in

the morning, Gigi and the other volunteers were gone. I don’t know where they

went, and I never saw them again, but I am grateful for their help. We could

not have gotten that crowd under control without them. Only one remained. The

first person to greet me was the tiny volunteer in the red cross shirt, with

the words, “Sir, these people still have not gotten any food.” I told her that the planes were going to

start coming in a few hours and then I bullied, coaxed and coerced the

Malaysians until they got food.

All the rest of the day I was

running back and forth, back and forth across the flight line, trying to find

Americans and other ex-pats, triaging the sick, wounded and elderly who wanted

to get priority on flights, arranging people in order to get on airplanes.

Every time I ran past her and her group I just saw more and more evidence of

her awesomeness. She pulled some of the older people and some ladies with

breastfeeding infants out of the crowd and constructed a little awning for them

to sit under. She asked me to take her family out on the next plane because her

sister’s baby was vomiting, but she assured me that she would stay behind to

help organize people. Sure enough, that is exactly what she did. I put her

family in the priority lane, and they were on the first plane out. She put

together the groups who would board the plane and sent them up by line of ten

when I asked her to.

The craziest rain I have ever seen

hit without warning, sometime around mid-morning. It was so thick you could not

see the planes on the tarmac. She simply stuck her purse (which was her only

luggage) under her shirt and kept working.

After the rain she made a deal with

the parents in the crowd. If they agreed to stay behind the gate and wait

patiently she would let the kids get out on the open cement where they could

have some fresh air and room to stretch their legs. Have you ever seen a group

of forty or fifty children sitting cross-legged in rows of ten, smiling and

happy, just because they can breathe freely? Sitting in one spot and not

moving, kept in check by just one tiny woman they have never met before in

their lives?

As the day wore on it became

obvious that she had taken those people to heart, literally. They were her

family and she took responsibility for them with all her might. Every group she

sent out to get on the airplane was a victory for her and somehow she made it a

victory for all of them. They were no longer fighting for their own survival.

They had become a family. I don’t know how she did it. She just did.

About 5:30 PM, just as the sun was going

down, she had another group of 40 people all set out in front of her gates,

squatting in rows of ten, waiting for their turn to board the C-130 that was

idling on the tarmac. Suddenly it happened again. The people at the main gate

panicked, broke through, pushed past the police and flooded the tarmac. They

completely swept past her and her group, blocking them off from the airplane. I

was moving in trying to find some police to help me restore order, and she

came rushing out to me with tears in her eyes. “Sir!” she cried. “Sir! These people!”

It was as if that was all she could

say. She eyed the huge crowd spread out between her people and the airplane

they had been waiting for for days and she looked on the verge of breaking

down. Looking behind her I could see her people still waiting, squatting in

rows of ten, frightened looks on their faces, but still waiting patiently,

trusting her to get them out.

I yelled in her ear. “I know. I am

sorry but there is nothing I can do about that. There are too many of them

now.”

She shook her head in desperation.

“Sir, my families?”

“Marina, there is nothing more you

can do tonight. I need you to find a safe place to rest for the night. We

probably won’t be loading any more planes, but you have been going all day and

you need some rest. I will try to find you later, and make sure these people

get food and water.”

She looked at me with a wry, half

amused look on her face. “My name is Marilee,” she informed me.

Well don’t I feel like a doofus!

She fell back to her people and the

crowd surged around her, and I lost track of her. For the next four hours we

were all busy trying to regain control and impose some sort of order on the

loading process. By the time I was able to look for her and her people again

the whole area was hopelessly crowded and finding one short lady in that whole

crowd was impossible. I simply had to pray that she was all right and leave her

to her own devices.

That was the night we finally cracked

the code and figured out how to load people at night without losing control of

them. There were some scary moments, but it went really well. It was almost

1:00 AM before I got to bed, and then I was up again by 5:00. I had some food

and did some work around our camp, cleaning up trash, reorganizing the

makeshift latrine (Oh, the glamorous life of an SF Medic!). About 6:00 AM

someone came to get me to tell me there was a local woman looking for me.

Sure enough it was Marilee. She was

wearing a different outfit because she had gotten the police to give her a

place to stay for the night and they had lent her some sweats to replace her

old clothes. She thanked me for getting so many people out last night, and

asked if more planes were coming in today. I said there were and told her that

she was going to be on the first one. “Go back to the flight line, and walk

about a hundred yards past where you were yesterday and you will see a gate

marked arrivals. That is the American passport line. You are going to be in

that line.”

“What if they don’t let me?” she

asked.

“Tell them Sergeant Kraeger sent

you,” I told her. “I will be along in an hour or so to make sure you get in

that line.”

She thanked me and headed back to

the airfield.

I headed back there about an hour

later, but to my surprise, before I got to the American line I saw her standing

at the same spot she had been standing yesterday, with a familiar looking group

of 40 people seated in rows of ten around her.

“Marilee,” I said, “I told you I could

get you out in the American line? What are you doing here?”

“Sir,” she said, “I found these families.” She gestured to the people waiting expectantly behind her. “They are

the ones from yesterday. Can I stay and make sure they get out?”

I tell you, my jaw nearly hit the

concrete. I don’t know if I have ever felt more humbled in my entire life. Here

she was after a full day and a half of taking responsibility for the well-being

of strangers she had never met before, coaxing them, encouraging them, bossing

them, caring about them. Now she had an opportunity to get out, free and clear.

She had earned it, as far as I was concerned, but she was willing to give it

up, just to stay with the people that she had adopted.

There and then I vowed to myself

that she and her whole group would be on the next flight if there was anything

I could do about it. I grabbed up the Marine Sergeant who was now running the

operation and introduced him to her and told him, “I don’t care what it takes,

this woman and this whole group with her get on the next flight. I don’t care

who is in the American line. She takes priority.”

That’s what happened. I was

transitioning to other missions, but I took a break to come back to the flight

line when the next American C-130 landed, to make sure she got on. That was the

only time she almost broke. When we loaded the first group of twenty, she was

left behind with the second group and a look of panic crossed her face. She

started to argue with the police, telling him that she had been promised, she was

with that group. When I came over to reassure her she was staring desperately

at the plane and she said, “Sir, I cannot do this another day.”

“You won’t have to,” I promised.

“You will be on that plane.”

The crew chief signaled, they sent

the next group, and she boarded with the last of her people.

It was strange. At one point the

day prior she had said to me in bewilderment, “I am not this kind of person. I don’t like to speak up to people. I do not know how I have the

nerve to do this. I don’t know why they do

what I tell them to. I am a nobody.”

I wish I had had time to explain

that I feel the same way. Most effective leaders do. Deep down inside we are

all faking it, pretending we know what we are doing, bewildered and intimidated

by the weight of expectation and trust placed on us, wondering how the hell we

ended up here. Why me? Why here? Why this job? Why not someone more dynamic,

someone better trained, someone more confident?

I did not have time for that. All I

had time to say was, “You care about them. People follow people who care.”

Labels:

America,

army,

Army life,

charity,

compassion,

disaster,

femininity,

human nature,

leadership,

Marines,

Philippines,

relief efforts,

Tacloban,

typhoon,

volunteering

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)